Those were the days when I was struggling to establish myself as a journalist. They used to call me Universal Correspondent since I had no authority to represent any particular publication. Still, I was busy from morning till night, moving about on my bicycle or on my neighbor Sambu’s scooter. I was to be seen here and there, at municipal meetings, magistrates’ court, the prize distribution at Albert Mission, with a reporter’s notebook on hand and a fountain pen peeping out of my shirt pocket. I reported on all kinds of activities, covering several kilometers a day on my vehicle, and ended up at the railway station to post my dispatch in the mail van with a late fee – a lot of unwarranted rush since no news-editor sat fidgeting for my copy at the other end; but I enjoyed my self-appointed role, and felt pleased even if a few lines appeared in print as a space-filler somewhere.

Those were the days when I was struggling to establish myself as a journalist. They used to call me Universal Correspondent since I had no authority to represent any particular publication. Still, I was busy from morning till night, moving about on my bicycle or on my neighbor Sambu’s scooter. I was to be seen here and there, at municipal meetings, magistrates’ court, the prize distribution at Albert Mission, with a reporter’s notebook on hand and a fountain pen peeping out of my shirt pocket. I reported on all kinds of activities, covering several kilometers a day on my vehicle, and ended up at the railway station to post my dispatch in the mail van with a late fee – a lot of unwarranted rush since no news-editor sat fidgeting for my copy at the other end; but I enjoyed my self-appointed role, and felt pleased even if a few lines appeared in print as a space-filler somewhere.

I did not have to depend on my journalistic work for my survival. I belonged to one of those Kabir Street families, which flourished on the labors of an earlier generation. We were about twenty unrelated families on Kabir Steet, each having inherited a huge rambling house stretching from the street to the river at the back. All that one did was to lounge on the pyol, watch the street, and wait for the harvest from the tenants. We were a vanishing race, however: about twenty families on Kabir Street and an equal number in Ellamman Street, two spots where the village landlords had settled and built houses nearly a century back in order to seek the comforts of urban life and to educate their children at Albert Mission. Their descendants, so comfortably placed, were mainly occupied in eating, breeding, celebrating festivals, spending the afternoons in a prolonged siesta on the pyol, and playing cards all evening. The women rarely came out, being most of the time in the kitchen or in the safe-room scrutinizing their collection of diamond and silks.

This sort of existence did not appeal to me. I liked to be active, had dreams of becoming a journalist, I can’t explain why. I rarely stayed at home; luckily for me, I was a bachelor. (Another exception in our society was my neighbor Sambu, who, after his mother’s death, spent more and more of his time reading: his father, though a stanger to the world of print had acquired a fine library against a loan to a scholar in distress, and he had bequeathed it to his successor.)

I noticed a beggar-woman one day, at the Market Gate with Siamese twins and persuaded my friend Jayaraj, photographer and framer of pictures at the Market Arch, to take a photograph of the woman, wrote a report on it and mailed it to the first paper which caught my attention at the Town Hall reading room. That was my starting point as a journalist.

Thereafter, I got into the habit of visiting the Town Hall library regularly to see if my report appeared in print.

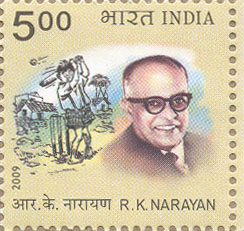

…………….. Talkative Man, by R.K.Narayan

P.S. Like any respectable South Indian character, Talkative Man, is simply referred to by his initial T.M. But he does have a real name. We get to know that in The World of Nagaraj .

He stayed back beside the two coconut trees over the dry gutter at the entrance. The Talkative Man went up and knocked at the door. The pundit appeared and greeted him with apparent pleasure. ‘Oh Ramu!’ he cried. ‘Where have you been all these months? So rare nowadays!’