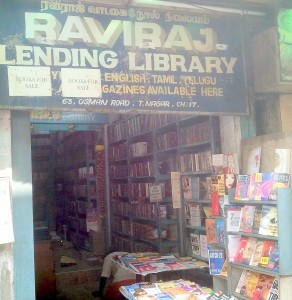

There is precious little for me to do in Chennai anymore. Most places I liked in my old neighborhood are gone: the quiet corner of a temple with a cannonball tree, the store that sells peanuts in newspaper cones, and the open-air market for flowers and fruits in a narrow lane off the bazaar. But the place which made a reader — I wonder if it is still standing. One evening, my feet take me there.

I used to borrow books from a lending library where cobalt-blue bookshelves ran from floor to ceiling. Our school library kept classics and encyclopedias locked up in glass-fronted cabinets. My parents didn’t see why students should read anything other than textbooks. Quite simply, they thought the concept of “story books” was a waste of time.

The owner of the lending library was a former waste-paper dealer. The city’s wealthy discarded books along with their monthly stack of newspapers — by the kilo. And the man set aside these discarded books and, often times, magazines as well. Soon, his clients began renting titles from that pile. The chance inventory clamored for a new home.

Past the stores that sold bridal saris and jewelry, he set up shop nearly five decades ago. He stands behind the register, chats with customers, and keeps an eye on everything around him. I don’t believe he reads anything — not even the Tamil magazines. Though he was no longer in the waste-paper business, he continue to stock used books from various sources.This is extreme recycling at work! I doubt these shelves have ever held a brand-new book. If his clientele don’t protest, what is the need to throw away good money on things like new books?

When I had visited this library for the first time, I was only in primary school. The staff clearly had instructions to shoo away lingerers, but me and my friends had to see what was on offer before we would put down our membership deposits. My friends and I decided to exchange books to maximize returns. By the time we finished high school, some of us became compulsive, if indiscriminate, readers. Then, we all went our separate ways.

And now I was back. On that busy commercial street, I strolled past multi-storied sari shops, all air-conditioned, with attractive window displays. My feet took me to the storefront with the cobalt-blue shelves. The owner was behind the counter. He had aged the way characters age in a school play: he wore outsize glasses and had some grey in a full head of hair. He didn’t seem to recognize me. Hesitantly, I began to browse. Then, I remembered. I had not claimed the refundable membership deposit of Rs.10 — roughly the equivalent of 25 cents — so technically I still belong though I no longer remember my membership number.

An uncle of mine had shuddered seeing me read one of these books . He mimed a borrower scratching his backside as he flipped through a magazine. I laughed but it didn’t make the slightest bit of difference to me. Where else would I get a steady supply of books?

In its heyday, this place served an assortment of members: men and women, young and old, those who read in the vernacular and those who read in English. It fulfilled its purpose. Now, there were mousetraps on the floor. Maybe, I had just never noticed the mustiness, the nth-hand books, and, yes, the clunky mousetraps before.

“Any particular title you want, Madam?” asked a voice, cutting into my reverie. It was the owner, with whom I’d haggled over the rental of a book many a time. Out of the corner of my eye, I see Manohar Malgoankar’s The Devil’s Wind and asked for other books by that author of princely sagas. “But this is his best book, Madam,” he said indignantly. A lit major with a dissertation on Malgoankar’s works couldn’t have sounded more convincing. Such titles used to be housed in a separate wing before, so I turn my head towards the flight of stairs. “Upstairs, sold Madam,” he said in a woeful voice but he did not look particularly sad about this.

We used to access that wing, unconnected to the main entrance, through a tricky staircase. Stray cats took shelter from the relentless sun, right by the landing. The staff shadowed us to make sure we didn’t make off with books without stopping at the front desk. Past the tailors’ stores, they followed us as if they had just remembered an important errand in the bazaar below. Occasionally, they caught a pilferer. “A person, who goes to school, should know better than to steal,” the owner would tell the offender.

The owner’s sons are educated and won’t inherit the business. Unlike the competition, he hasn’t computerized operations. “Nobody reads anymore Madam,” he tells me with a shrug.

Why does he bother to run the place at all, I wonder. The age of Kindle is upon us anyway. Just then a patron wanders in to ask for the latest issue of some magazine. Someone has checked it out. She doesn’t seem to particularly care. She sets down her grocery bags, and begins chatting with the owner about this and that. Moving to the topic of grown children, they bemoan the habits of this generation at some length. Maybe, this is reason the place is still open — it allows the owner to socialize.

Dusk is falling fast. In this newly prosperous city, traffic gets impossibly chaotic during rush hour. I have a feeling the library won’t be there the next time I visit — some textile retailer would annex the space. This is Chennai’s Saks Fifth Avenue after all. Near the exit I see a shelf with the label “Unknown Bestsellers.” What does that mean? Bestsellers which are not as well known as they should be in these parts? Who told the owner about them?

Unfortunately, I cannot linger on to find out more. The crush of evening shoppers will descend on the main road any minute now. The very thought fills me with panic. Hailing a passing auto-rickshaw, I head home.

En route is Nalli’s, where Supermodel Padmalakshmi supposedly buys silk. She is in town, the newspapers have reported this week. Does she actually shop with the masses or is just the kind of thing a celebrity tell a reporter? I keep my eyes open but, of course, I don’t spot her among the throngs that evening . I hope no relative of mine has spotted me either in this gossipy old town.

Related links:

- The New Yorker story by Salman Rushdie featuring the real-life tsunami that struck Madras .

- Love, loss and dosas