If you want to be fluent in a language, experts say, you should relocate, briefly, to a place where the language is spoken exclusively. It will force you to find the words to interact with the locals — that is the immersion method. Maybe, the reverse is true for reading in your mother tongue. I read my first novel in Tamil, my mother tongue, very far from home. I had just moved to the United States to do a graduate degree in chemistry.

At the university, I attended classes and taught a lab course during the day. I’d leave at 5 PM, and after an early dinner, I would return to the department to do my research work. I’d set up a reaction that could take hours to run. While this was underway, I’d grade lab reports or step into the hallway to chat with students from other labs. Truth is most graduate students, both American and international, had a life outside the department. So most evenings, the place was silent except for the hum of the lab equipment.

Homesickness hit hard that first semester, though I did not recognize it as such. In the late 1990s, there was no social media, but there were mailing lists. I could connect with college-based acquaintances. One day, unexpectedly, I found my friend’s mother online. I knew her during my undergraduate days in Chennai, a pleasant presence in the background. She now lived near Washington D.C. We began exchanging emails. She was an aficionado of popular literature in Tamil but like many other language orphans in India, I had not learned my mother tongue in school. I could barely read the Tamil script, I told her. The wise woman knew exactly what to do.

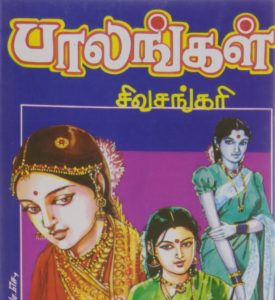

Just before winter break, when the campus turned into a ghost town, she mailed me a Tamil paperback titled “Paalangal,” meaning bridges written by Sivasankari. This family drama featured women of different generations across the 20th century. Its recurring theme was that with age, even brash young women turn into metaphorical “bridges” who would hold the members of a multi-generational family together. The characters spoke like my relatives. Some even had the same old-fashioned nicknames – etchumi for Lakshmi, sachchu for Saraswathi, and papli for heaven knows what – which made me laugh out loud. When any of these characters started a sentence, I could finish it in my head. Then, I’d read the text to see if I had it right. Thanks to this “auto complete” feature, I finished reading the book a lot faster than I expected. I mailed the book back with gratitude.

Like the human equivalent of a clever recommendation algorithm, my friend’s mother gave me suggestions. There was the memoir-like book (Srirangathu Devadhaigal) by engineer-author “Sujatha” Rangarajan in which he chronicles growing up in the temple town of Srirangam. I loved reading about that cricket match, thanks to which the cerebral author’s name appeared in the sports pages of The Hindu, for the first and last time. The book remains an all-time favorite.

As writer Sujatha Rangarajan mentions in the preface to his memoir-like work “Srirangathu Devadhaigal,” a straightforward description of real-life incidents can be boring. You need a few additions to make the story interesting. But how much of a fictionalized narrative is fact and how much is fiction is a trade secret which a good writer will never give away.

I found a series of Appusami stories by Bhagyam Ramasami featuring an old couple. Sita Patti [full name: Sitalakshmi Appusami], a madisar-clad sixty-plus bombshell, the president of a ladies club called PMK (Patti Munetra Kazhagam). Patti keeps her husband, the Madras-Basha speaking Thatha, (real name: Appusami), busy with work around the house. This makes Patti look like a despot but the errands keep Thatha out of trouble.

What trouble can an eighty-plus man get into, you ask? Well, for that you have to read the kite-fight episode or about the time when Thatha, a Kushboo fan, had the actress’s name tattooed on his chest. The convent-educated Patti peppers each sentence with English words. So these books were a breeze to read, besides being a total hoot. ROTFL.

Listen to: Come On, Appusami, C’mon

Some classics too I found on my own. I stumbled upon the black-and-white film based on Jayakanthan’s 1970s novel whose title translates to “Some People in Some Situations.” The book grew from the conservative backlash to Jayakanthan’s short story “Agni Pravesham” about a young ingenue who is seduced by a rich, married playboy. The author took the vitriol and created an award-winning novel . He put the short story at the core of the novel, he gave himself a role in the book, featuring as a librarian at a woman’s college and part-time writer. The complex structure of the novel is a topic for an academic thesis, but the book is not a difficult read, if you can deal with realism. Or just watch the movie first.

One day, I was finally ready to embark on the adventure of reading the multi-volume historical fiction, by “Kalki” Krishnamurthy, featuring the eleventh century emperor Rajaraja Chola I. The story was serialized in a magazine in the 1950s, so chapters tended to end with cliff-hangers. Maybe, I was being too ambitious trying to read this now – so far removed was I from the story in terms of time and distance – I thought. But very soon, I was on horseback, a third rider galloping through the ancient landscape with the protagonists, the prince and his friend. When I finished all five books – over 2000 pages in total — within a few months, my mother couldn’t have been prouder of me.

What have I achieved with all this desultory, non-literary reading over the years? Ancient poetry in Tamil remain inaccessible to me except in translation. Still, the fragments of Tamil I’ve acquired over the years have added up to something substantial. Words of old prayers now make sense to me. So do the lyrics of old film songs, which include the verses of revolutionary poet Bharathiyar. The incantatory power in his words enthrall me; they give me strength. On this, I think most will agree with me: Bharathiyar can be Bharathiyar only in Tamil.

They say you are never alone in the company of books, but, of course, you should be able to read them first. I am glad I made the effort to interact with some fictional characters in a Tamil paperback novel. That investment has paid me some decent dividends over time.